Notes on the Film

As explored in a companion documentary to this film that you can watch here, Jon Deak’s The Passion of Scrooge feels like a pinnacle not only of Jon Deak’s work, but also of Charles Dickens’ own, transfiguring the venerable literary masterpiece into this consummate medium of opera. Jon’s score combines emphatically contemporary idioms, with classically tonal and unambiguously emotional arcs. Musical leitmotifs shape the instrumental parts (and the musicians who play them) into narrative characters, deploying Jon’s distinctive technique of “Sprechspiel” (“Speak-playing”). Inventive and endlessly fresh, these compositional values also align with the old-time virtue of radio plays, where the listener was freer to roam in imagination…and visualization.

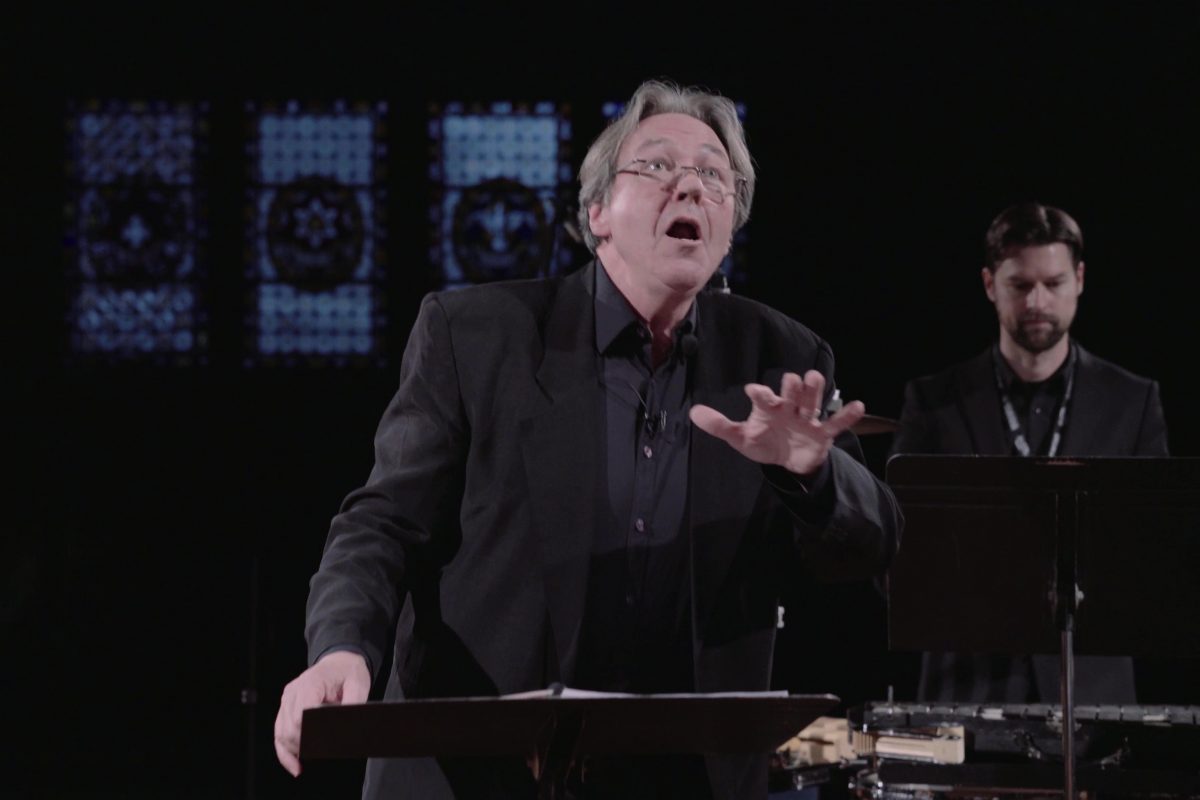

Adapting any opera to film runs the risk of neglecting that essential virtue, especially from the “musicals” playbook: a movie musical usually materializes music into the precise world of its story, from costumes to sets to locations. What ultimately evolved as a guiding instinct for this adaptation, though, began years ago from the film project that first introduced me to the 21st Century Consort and baritone William Sharp: my documentary portrait of composer Samuel Barber (samuelbarberfilm.com). As Bill and the Consort started off the film with Dover Beach, that melancholy masterpiece triggered a fascination that asks: what is the story behind a composer’s work? Why such struggle (besides the technical effort)? When does a composition become perfected, and who can decide? Does life itself decide? And why does regret haunt music so much?

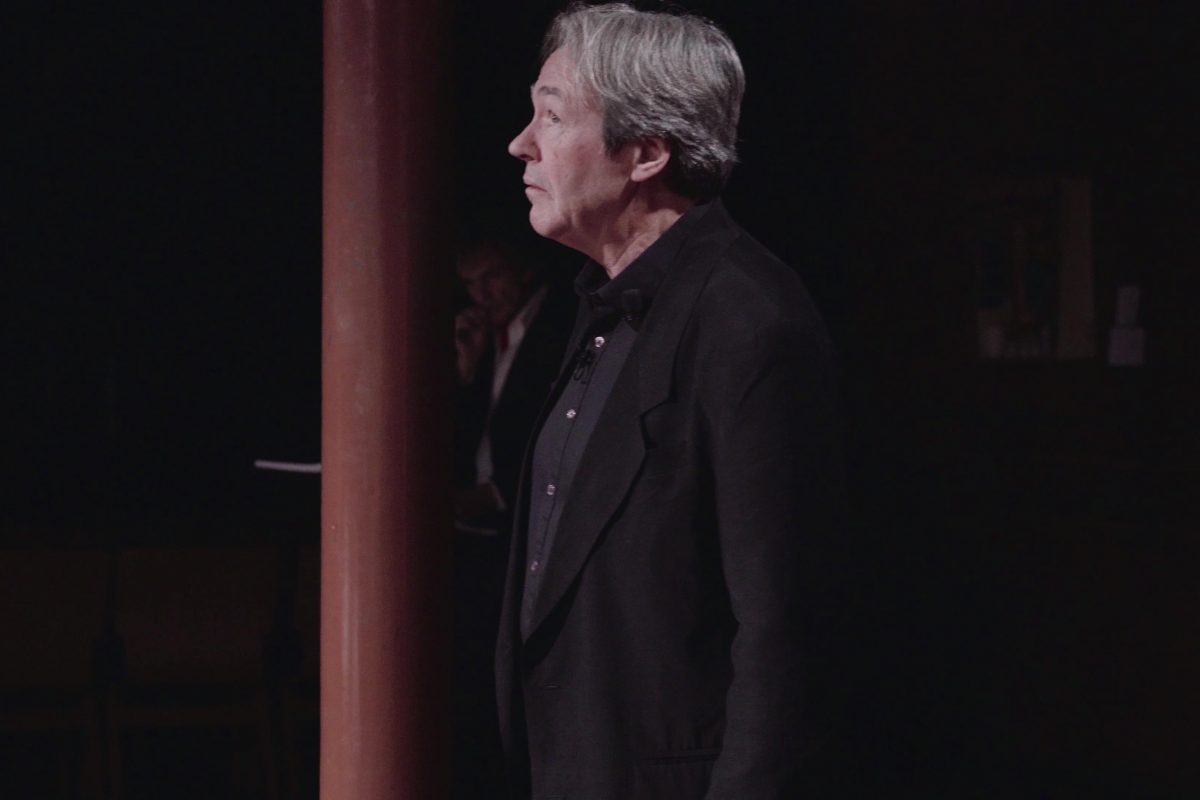

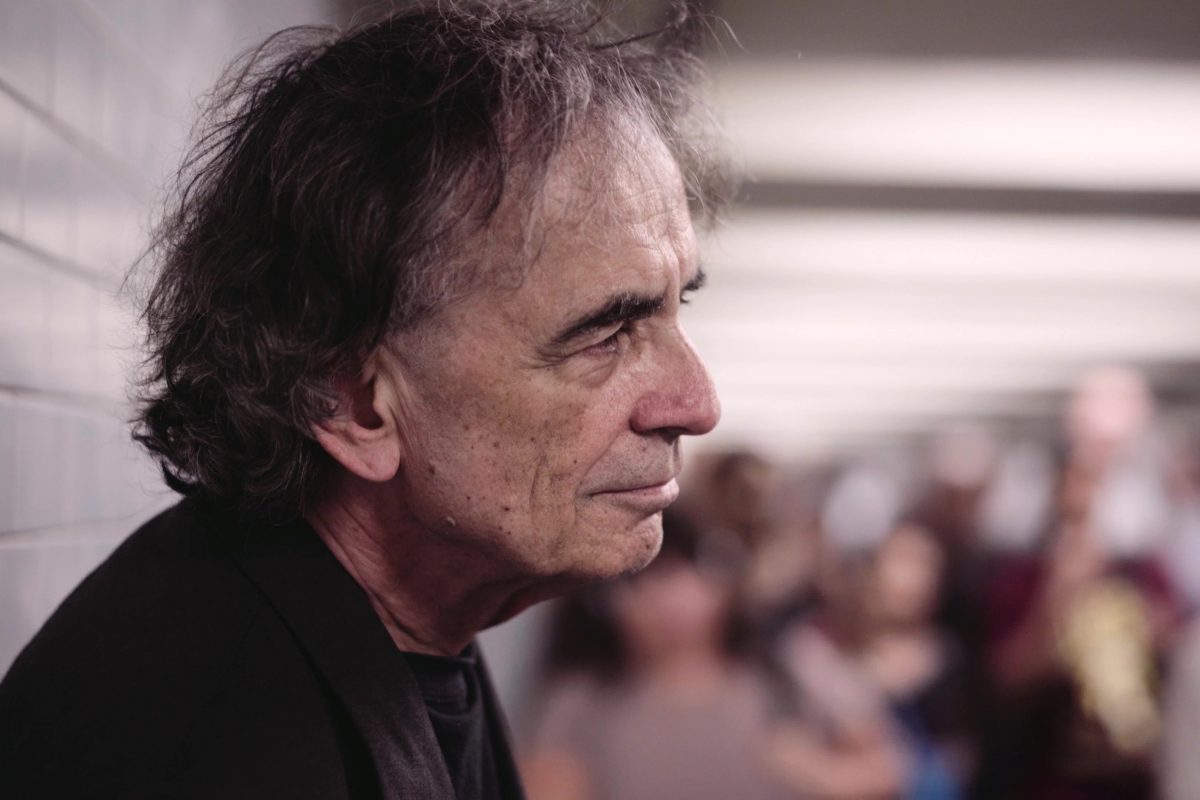

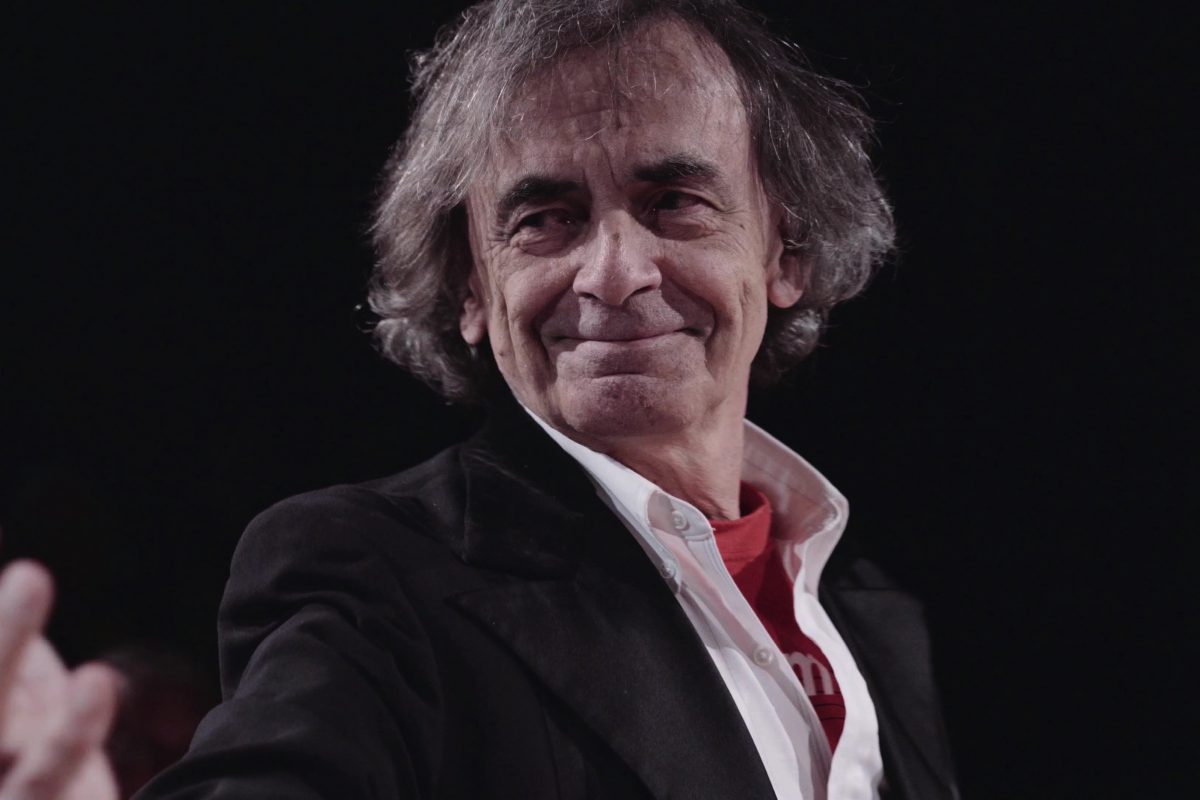

The nearly archetypal character of Scrooge conceived by Dickens can stand in well for the trajectory of a composer’s life. Upon meeting Jon Deak, it took almost no time to see that his striking mien, skill at performance art, and biographical resonance with this work, would need to haunt every scene. In a sort of conceptual twist: he might be alive or dead; we might be seeing the opera’s origin or reckoning; the audience and musicians might be imagined or real; the singer and composer, and even conductor might or might not be the same person. That kind of fluidity is the open space accorded by all those radio plays of olde, and revived here in a cinematic opera.

Risks get taken in this film, besides its essence as a concert – including a Prologue and Entr’acte that exceed the borders of the piece, while navigating genre boundaries between documentary, narrative cinema and magical reality. Meantime, my “floating” cinematography presents intimate, intuitively free-roaming views of the chamber players, perhaps unlike anything yet seen for traditional instruments. This project also inspired upscaling and restoring an early (and neglected) film from 1935 that fell into the public domain, for occasional incorporation into this film as an archival veil over the performance. From that effort of subtly applying latest-technology flicker/grain reduction, and audio expansion/noise reduction, it is a companion to this project in hour-long form, becoming the best available version in existence. The 1935 film does not rank among the most acclaimed Dickens adaptations, but its historical distinctions include several moments of expressionist camerawork unique to the Dickens canon, while also being the first sound film version of A Christmas Carol.

— H. Paul Moon, director