Notes on the Opera

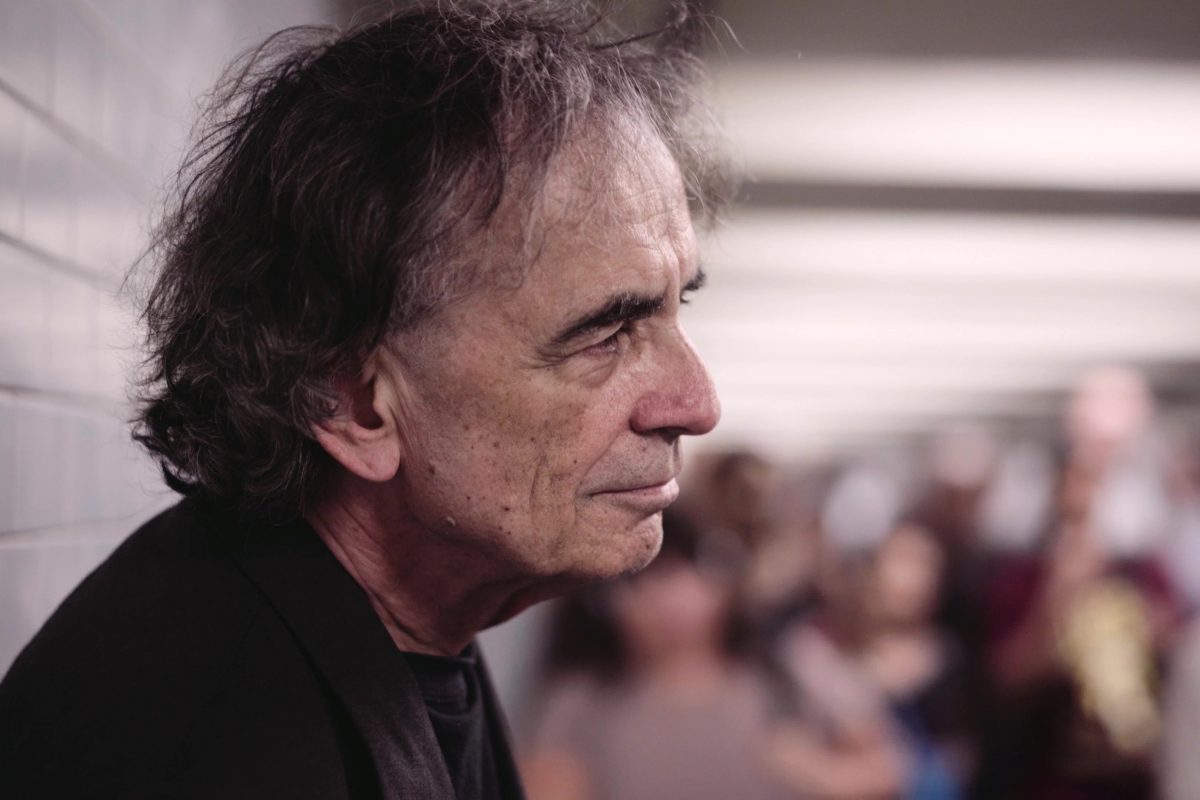

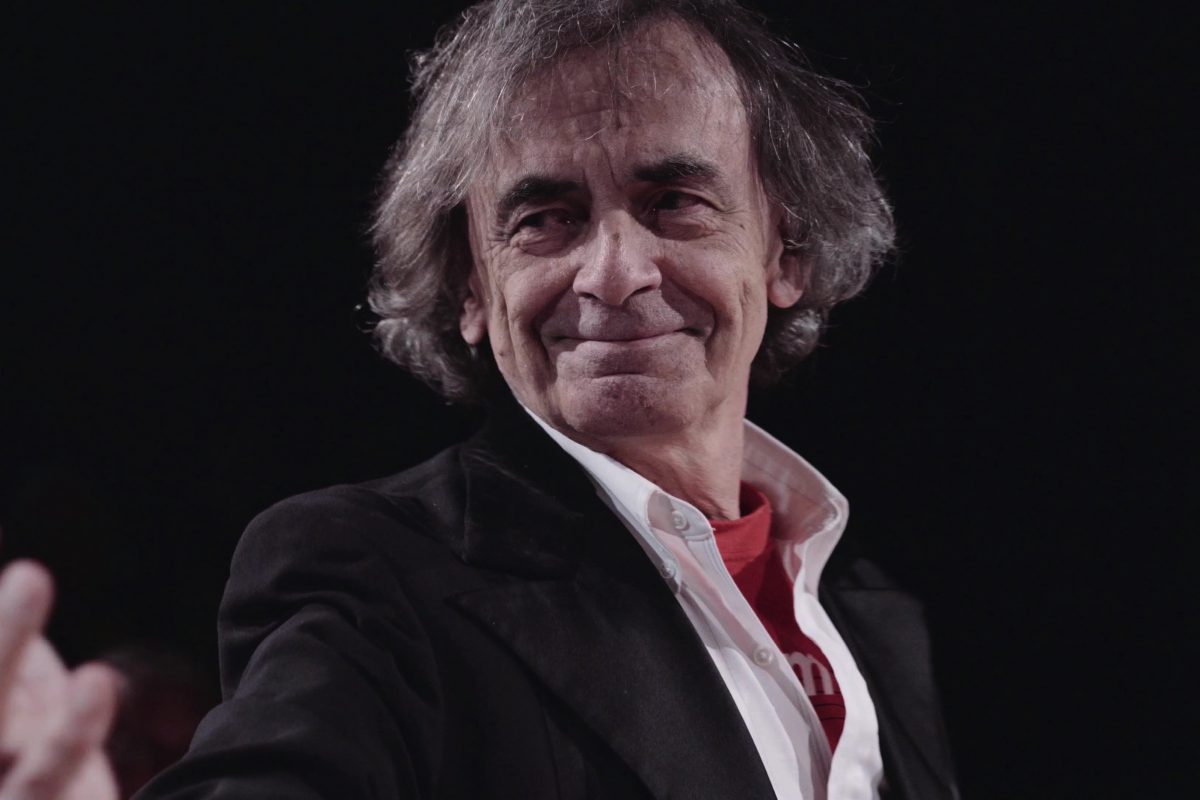

Jon Deak was born in Hammond, Indiana on April 27, 1943. He grew up in an artistic environment. His father and mother were sculptors and painters; he himself has worked in sculpture. But music seized his attention; he studied double bass and composition at Oberlin, Juilliard, the Conservatory of Santa Cecilia in Rome, and the University of Illinois. The greatest influence on his work has come from Salvatore Martirano and John Cage and from the Soho performance art movement of the late 1960s and early 70s. Since 1970, Deak himself ha[d] been a member of the double bass section of the New York Philharmonic. Spending much of his professional life as a performer has no doubt contributed to his interest in what is known as “performance art” — a creation that involves more than simply the notes on the page, that comes alive only in the person of the executants.

Of course, all music is really a performance art: the printed score is not the work, but only a blueprint of it. But Jon Deak’s works, many of which have been performed by the [21st] Century Consort, are performance scores in a different sense; the work has a visual and theatrical element that transcends the customary relationship of pitch and rhythm. They are a kind of “Story Theater,” to borrow the name of a theatrical performing company of the 1970s that produced elaborate versions of fairy tales in which actors began by narrating (as outsiders observing the story), then gradually became the characters they had been describing. Similarly, in Jon Deak’s many “concert dramas” (the term he has come to prefer for this kind of work), there can be soloists who both narrate and enact the story, and the instrumentalists themselves take part in various ways, both by word and sound.

On several occasions Deak has turned to an old story-whether folktale or, as here, a work of literary fiction. Other examples in his output include The Ugly Duckling, The Bremen Town Musicians, and Lucy and the Count (based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula). All partly make use of speech rhythm for the music. The words of the tale are turned into music, which sometimes takes over the storytelling entirely and sometimes supplies the background to declamation. The instrumentalists evoke words “woven into the music as a sound event.” As the composer has explained, he is sometimes “more concerned with the sound event than with the meaning of the words.”

A Christmas Carol is the longest of these musical narratives. It also took the longest time in composition. The idea for the project first arose in 1986, partly through the mediation of Christopher Kendall, but was not finished then. Deak states: “Then Jack and Linda Hoeschler approached Christopher Kendall and me about completing this project. It turned out to be a big piece — and they have been very patient! As I worked further on it, my point of view changed. I started adapting the original libretto, which was by Isaiah Sheffer, and as I continued to work on the piece, I made more and more changes from the first version, so now the libretto is essentially by me, though it retains some of Isaiah’s work, and of course we both based what we did on the Dickens story [1843]. The piece turned out to be a work for baritone and chamber ensemble because I felt that it was best to have just one person up there. I think it works out perfectly that way because, in this story, all the characters come out of Scrooge’s head — the whole drama takes place within his head. If we had other characters singing at Scrooge it would be didactic: society putting pressure on him to reform. But this way it is internal, depicting his own struggle. That’s why I changed the title to something that sounds rather Dickensian in style: The Passion of Scrooge, or A Christmas Carol.”

The piece is cast in two acts. During the first we are introduced to Scrooge and his departed partner Marley, who comes as the first Christmas Eve ghost to warn Scrooge that he must change his grasping, greedy ways. (Though the instrumentalists in the ensemble become various people, the baritone is both Scrooge and Marley, who at this stage of the story represent a single vice, avarice, in two different bodies.) The second act introduces the three ghosts of Christmas — past, present, and future — who help Scrooge experience his passion and accomplish his transformation.

— Steven Ledbetter

NOTES BY THE COMPOSER

Roughly the first five minutes of the piece as it now stands were composed in 1986, the next ten minutes in 1996, and the remainder of the score in 1997. The music of Scrooge and Marley, those outcasts from human warmth and expression, operates with tone rows, or segments of tone rows, while the remaining characters (and, gradually, Scrooge himself) are more tonal, even romantic in character. Scrooge is constantly testing new self-images, and his music is constantly changing, though it is built out of a half-dozen different motives, some of them interrelated.

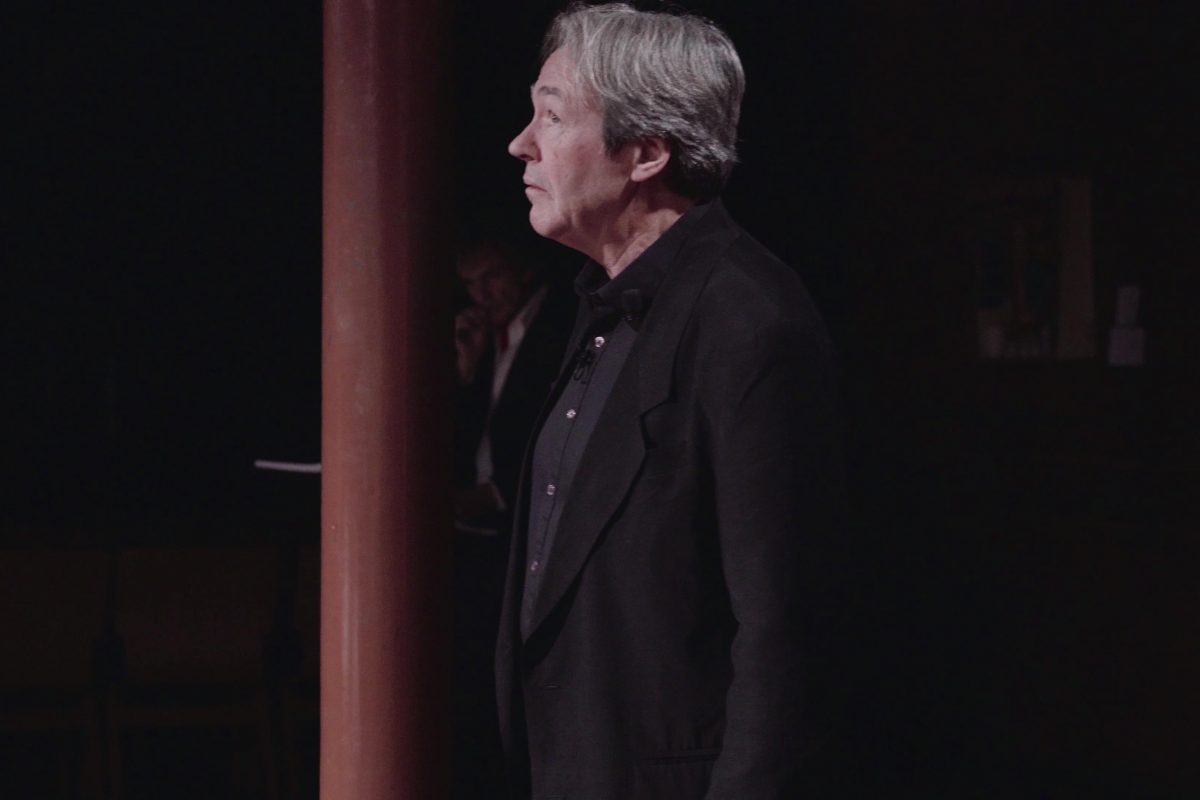

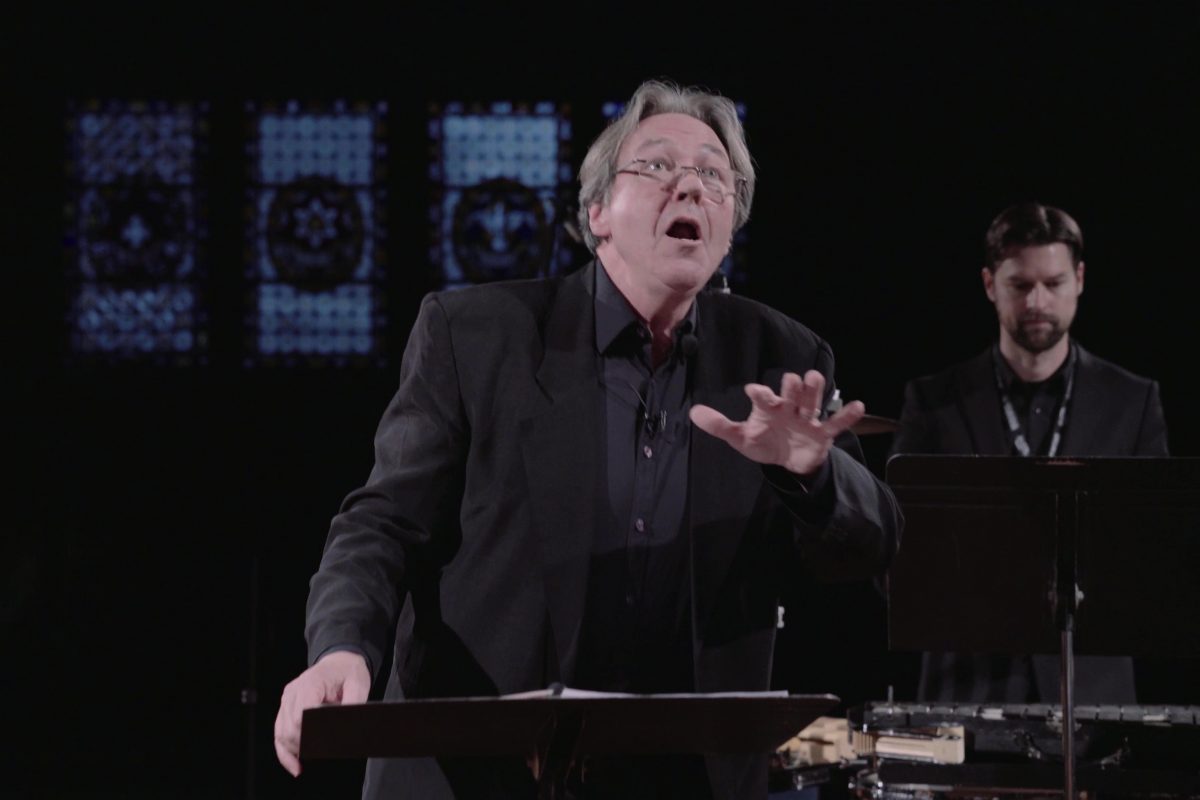

The circumstances surrounding the first performance on December 6, 1997, at the Hirshhorn Museum were extraordinary; for one thing, finishing the work in time was proving to be an agony. I’d been giving the score piecemeal to Bill Sharp and Christopher Kendall over the course of several months, but due to several unforeseen reasons, they never actually got the complete score until (incredibly) four days before the concert! Bill was up literally all night for the sixty hours preceding the performance. In addition, I was a real pest, badgering him, questioning with him, working out ideas about how the characters should be conceived, changing notes, tempi, dynamics, hand gestures, facial expressions, and dissolving into confused babbling. Bill and Christopher were unbelievably calm and supportive throughout, often turning my wild suggestions into something much more effective than I could have conceived.

I was also a pain-in-the-neck to the performers, since, as the storyteller says at the very beginning: “…and all you musicians are going to play parts in the story.” Well, I took that seriously. But to expect musicians to embody roles in a story without resorting to costumes, props or fancy (amateurish) gestures is a lot to ask, yet I was never disappointed. At times the musicians had to react with vocal wind, insidious whispering, actual words, outright laughter or even – singing “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen” as if they were roistering carolers. Indeed, the very opening sound of the entire drama is an intake of human breath sounding perhaps like an ancient wine or fog lifting – my sonic equivalent of a stage curtain rising.

In addition to playing the motives of the various characters, each musician needs to, as I say, embody them, often imitating human speech on the instrument in a technique I refer to as “Sprechspiel,” or “Speak-playing.” Sara, the flutist, plays such roles as a woman in the London street, echoes of the lost fiancé of Scrooge’s youth, as well as aspects of Scrooge himself. Loren, on clarinet, is a little boy outside Scrooge’s window on Christmas morning and, on his bass clarinet, Scrooge’s darker feelings. Ted’s “horn-of-plenty” embodies the Ghost of Christmas Present; Dotian’s harp, that of Christmas Past — and the baritone soloist actually converses with these characters. David Salness with his violin plays a gentleman soliciting charity for the poor, Scrooge’s nephew, as well as aspects of Tiny Tim. Daniel Foster’s viola is Bob Cratchit; David Hardy’s cello, the apparition of Marley; Robery Oppelt enacts Scrooge’s depression with particular vividness on the double bass. Tom Jones, the Consort’s percussionist, is a one-man stage set and sound-effects man, with imaginary scenery. He even provides the parrot “squawk” for Robinson Crusoe. David Salness’s violin later becomes Scrooge’s magical (no other word for it!) ascent from a mean depressed old man to a magnificently reborn soul on Christmas Morning. That we were able to capture this particular moment of performance artistry on this recording will probably remain one of the great joys of my life. It is the crux of the entire work and, I admit, my favorite part.

But back to the first performance… Here we have a sleepless Bill Sharp imbued with the responsibility of carrying all this drama on his shoulders. And there we have myself, the tardy composer, whispering suggestions to him and to Christopher right up to 10 minutes before the concert. Finally, I settled back in the audience, with my daughter Selena sitting in my lap. Next to me were Christopher’s wife Susan and, a few seats away, Jack and Linda Hoeschler, Inge Cadle and Bill and Nancy Foster, all of them so helpful at crucial points along the way. Notably absent was Nancy Foster and Christopher Kendall’s wonderful mother Catherine, who had passed away days before. We dedicated the first performance to her. In any case, to say we were all nervous would have been an immense understatement. But, as Christopher started the overture, I could hear that things were already sparkling. And as Bill Sharp took his breath for his very first entrance, my jaw began to drop: I could tell immediately that he had done it! He was completely in character, right on pitch, and remained in mastery until the very last note. How did he (and they) do it? Who knows? I’ve never been so amazed at a performance, and so glad I’d become a composer.

The Washington Post seemed to agree about the success saying:

“Deak’s thorough retelling of A Christmas Carol is a marvel of musical ingenuity…it was one of the most vivid and memorable concerts I have attended this year.

“Deak has taken up the story of Scrooge with zest, vigor and the kind of narrative skill that has won him a substantial and devoted audience. It was, as Deak’s music usually is, technically brilliant and a lot of fun.

“William Sharp rose to the role of Scrooge with magnificent zest and skill.”

Redemption is so precious. As Tiny Tim says: “God bless us, God bless us everyone!”

— Jon Deak

The Passion of Scrooge was commissioned by Jack and Linda Hoeschler in honor of Inge Cadle and in memory of Don D. Cadle. The score is also dedicated to the composer’s mother, Mary-Ellan Jarbine.